“The City on the Edge of Forever”

Written by Harlan Ellison

Directed by Joseph Pevney

Season 1, Episode 28

Production episode 6149-28

Original air date: April 6, 1967

Stardate: unknown

Captain’s log. The Enterprise has detected waves of time that cause turbulence in space, making for a risky orbit over the planet that’s the source of the waves. The helm overloads, injuring Sulu badly enough to cause a heart flutter. McCoy gives him a small dose of cordrazine (which Kirk describes as “tricky stuff”). Sulu’s fine, but another bit of turbulence causes McCoy to stumble forward and inject himself with the entire vial, which sends him into an adrenaline-fueled, drug-induced panic. He runs from the bridge, screaming about assassins and murderers, and goes to the transporter room, taking out the chief and grabbing his phaser, then beaming down to the surface.

Kirk takes a landing party that also includes Spock, Scotty, Uhura, and two security guards. Spock reports that the ruins are 10,000 centuries old. At the center of it all is a giant ring, which is apparently the source of all the time displacement, even though it just looks like a big stone ring.

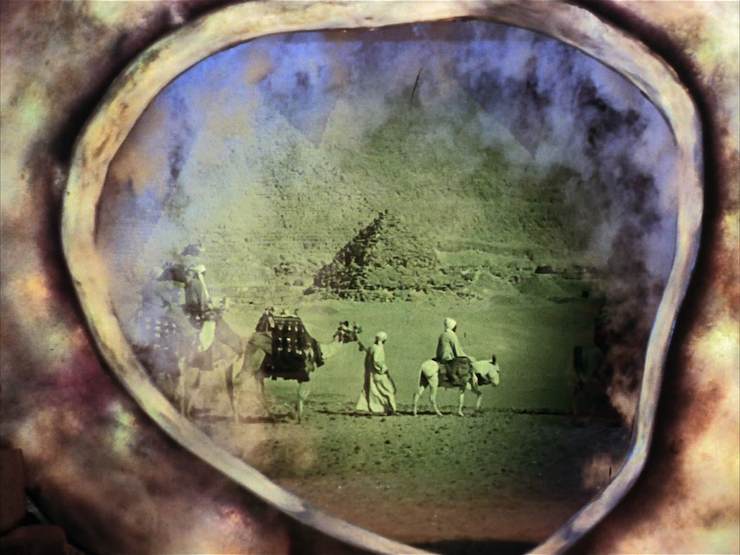

When Kirk asks, “What is it?” the stone ring actually answers, saying it is the Guardian of Forever. It is a portal through time, and to prove it, the portal shows images from Earth’s history.

McCoy is found and stopped by the search parties, rendered unconscious by Spock’s nerve pinch. Kirk ponders whether or not they could go back in time a day and stop McCoy from injecting himself, but the centuries are zooming by far too fast for that to be practical.

However, as they are transfixed by the Guardian’s quickie view of Earth history, McCoy wakes up and dives into the portal before anyone can stop him.

Uhura was in the middle of a conversation with the Enterprise, but the communicator went dead once McCoy jumped through. The Enterprise is no longer in orbit—somehow, McCoy changed history when he went back in time.

Spock was recording with his tricorder when McCoy leapt through, and he is able to approximate when to jump—within a month or so of McCoy’s arrival, he hopes. Kirk orders each member of the landing party to wait as much time as they think is wise and then take a shot at it themselves. At worst, they’ll be able to live out their lives in the past.

They find themselves in New York during the Great Depression. Their anachronistic clothing and Spock’s ears get them lots of funny looks, and their theft of clothing gets the attention of a uniformed police officer. Kirk thumphers around trying to explain Spock’s ears before Spock finally takes pity on him and neck-pinches the cop. They run away to the basement of a mission, where they change clothes, including a nice wool cap for Spock.

The mission is run by a woman named Edith Keeler, who hires them to clean the place for fifteen cents an hour. That night, they go to the mission’s soup kitchen for dinner, for which the “payment” is to listen to Keeler speechify. She speculates quite accurately about the future—predicting atomic energy and space travel—and Kirk finds her captivating.

Keeler also provides Kirk and Spock with a room for two dollars a week. Over the next several weeks, Spock endeavors to construct a computer to link up with the tricorder so he can view the images on it, but the primitive equipment of the era combined with their meager salaries makes the work slow and difficult.

Spock steals some tools to aid in his engineering project. Keeler not only catches him at it, but can tell that they don’t belong there, and that Spock belongs by Kirk’s side. Keeler lets them off the hook only if Kirk will walk her home.

Eventually, Spock’s work serves him well. He finds that Keeler is the fulcrum. In one strand of history, Keeler meets with President Roosevelt in 1936; in another, she is killed in a traffic accident in 1930. The problem is, they don’t know which one is the proper time frame—Spock’s jury-rigged mess of a computer burns out before he can determine that, and it will take time to fix. What worries Kirk—who is falling in love with Keeler—is that she will need to die to restore the timelines.

McCoy shows up, still in his cordrazine-induced haze. He finds a bum who is in the midst of stealing a jar of milk, eventually suffering a total breakdown and collapsing. The bum searches McCoy’s unconscious body, but only finds the phaser he stole from the transporter chief, which he then uses to disintegrate himself.

The next morning, McCoy, still a mess, wanders into Keeler’s mission. She puts him on a cot to recover.

Spock finally gets his doodad working again, and the news isn’t good: because McCoy did something to save Keeler from dying in a traffic accident, she goes on to form a very influential pacifist movement, one that slows the United States entering World War II. Because of that, Nazi Germany is able to develop the atomic bomb first and use it to win the war. Keeler was right in general—peace is better than war—but her timing sucked, as it led to fascists ruling the Earth.

Keeler continues to care for McCoy, who assumes he’s demented or unconscious, refusing to believe that he’s really on “old Earth” in 1930. She brings him a newspaper and he offers to do some work around the mission to thank her. She says they can talk about it in the morning, as she’s going to a Clark Gable movie with “her young man.” McCoy has no idea who Clark Gable is, to Keeler’s shock.

She meets with Kirk, and he has the exact same confused reaction to the name Clark Gable, which leads to her mentioning that “Dr. McCoy said the same thing.” An elated Kirk is thrilled to learn that McCoy is in the mission, and he runs back across the street to grab Spock—and then McCoy comes outside and everyone’s happy to be reunited. A very confused Keeler wanders into the street, and doesn’t see the car barreling down on her.

McCoy moves to save her; Kirk stops him, and they watch as Keeler is killed. McCoy is appalled that he let her die, but Spock assures McCoy that Kirk is quite aware of what he did.

The trio return through the Guardian (which apparently gave them time to change back into their uniforms). From the landing party’s perspective, Kirk and Spock only left a moment ago. But the Enterprise is back in orbit, and so a grim Kirk says, “Let’s get the hell out of here,” and they beam back.

Can’t we just reverse the polarity? The Guardian is both alive and a machine, which it says is the best way it can explain things based on how inferior Federation science is. Spock is somewhat offended by that.

Fascinating. Spock refers to technology he is forced to work with in 1930 New York as akin to “stone knives and bear skins,” which would take root in popular culture as an expression relating to primitive tech.

I’m a doctor not an escalator. McCoy is in a full-on paranoid haze for most of the episode, and even when he recovers, he thinks he’s still having delusions, based on the fact that he doesn’t believe that he’s in 1930.

I cannot change the laws of physics! Scotty takes over the helm after Sulu is injured, and joins the landing party for no compellingly good reason.

Hailing frequencies open. The role of recording the landing party missions that used to go to Rand, and then went to the various yeomen who followed her, now falls upon Uhura, who is also the one who stays in touch with the Enterprise on the landing party. It’s not much, but at least she gets off the ship for a change.

Ahead warp one, aye. Sulu is badly injured enough to warrant being injected with cordrazine. The goofy smile he has when he wakes up indicates just how good a drug it is…

Go put on a red shirt. Despite being on high alert, security utterly fails to stop McCoy from entering the transporter room and beaming down to the surface.

No sex, please, we’re Starfleet. Kirk and Keeler fall pretty hard for each other. It’s actually very sweet.

Channel open. “Since before your sun burned hot in space and before your race was born, I have awaited a question.”

The Guardian’s very poetic way of introducing itself.

Welcome aboard. John Harmon plays the bum who is disintegrated by McCoy’s phaser, Hal Baylor plays the cop, and Bartell LaRue does the voice of the Guardian. Enterprise crew are played by regular guests John Winston and David L. Ross alongside recurring regulars DeForest Kelley, James Doohan, Nichelle Nichols, and George Takei.

But the big guest, of course, is the radiant Joan Collins, already a lead in several films throughout the 1950s, a regular guest on several shows in the 1960s, and whose most famous role (probably even more so than her role here, though it’s close) was as Alexis Carrington in Dynasty during the 1980s.

Trivial matters: This has consistently been at or near the top of pretty much every list of best Star Trek episodes. Indeed, most lists of top episodes of the original series have this and “The Trouble with Tribbles” occupying the top two slots. In 2009, TV Guide ranked it at #80 in their list of top 100 TV episodes of all time. (That same list had TNG‘s “The Best of Both Worlds Part I” at #36.)

Harlan Ellison’s script was, rather famously, rewritten—Stephen W. Carabastos, Gene L. Coon, D.C. Fontana, Gene Roddenberry, and Ellison himself all took passes at it, with Fontana’s draft being the one that was primarily used, though Ellison retained credit. Roddenberry refused to allow Ellison to use his pseudonym “Cordwainer Bird” for the episode. (Ellison has always used that pseudonym when he felt he was rewritten unjustly.) The feud between Ellison and Roddenberry over the rewrites continued until the latter’s death.

This episode has the only use of “hell” as an expletive in the series.

The quickie views of history through the Guardian are mostly clips from various old Paramount films.

A poster is seen advertising a boxing match between Kid McCook and Mike Mason in Madison Square Garden. A poster advertising their rematch is visible in a scene taking place in San Francisco in 1930 in the DS9 episode “Past Tense Part II.”

Ellison’s original script—which won the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Written Dramatic Episode—can be found in his 1996 book The City on the Edge of Forever: The Original Teleplay that Became the Classic Star Trek Episode. In addition, IDW recently adapted Ellison’s original script into comic book form, with art by JK Woodward.

The final version of the episode won the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation in 1968. All five nominees in that category were Star Trek episodes, the other four being second-season episodes “The Trouble with Tribbles,” “The Doomsday Machine,” “Mirror, Mirror,” and “Amok Time.” That was a good year for Ellison, who also won for Best Short Story (for “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream”) and was nominated for Best Novelette (for “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes”; he lost to Fritz Leiber’s “Gonna Roll the Bones”).

James Blish’s adaptation in Star Trek 2 used elements of both Ellison’s original script and the final draft.

Bantam’s first-ever fotonovel was an adaptation of this episode, which also included a short interview with Ellison.

The Guardian of Forever will show up again in the animated episode “Yesteryear.” It also plays a role in tons of tie-in fiction, among them The Devil’s Heart by Carmen Carter, Imzadi by Peter David, Yesterday’s Son and Time for Yesterday by A.C. Crispin, Crucible: McCoy: Provenance of Shadows by David R. George III, and bunches more. George’s novel explores the alternate timeline created by McCoy going into the past in which World War II ended differently and there was no Federation, following McCoy’s entire life in the 20th century in that history. The Guardian is also seen in issue #56 of Gold Key’s Star Trek comic by George Kashdan and Alden McWilliams, as well as issues #53-57 of DC’s second monthly Star Trek comic, a storyline entitled “Timecrime” by Howard Weinstein, Rod Whigham, Rob Davis, and Arne Starr. The Guardian is also used in the Star Trek Online videogame.

William Shatner chose this episode as his favorite for the Star Trek: Fan Collective: Captain’s Log DVD set.

To boldly go. “Let me help.” The writing process is a tricky thing. There’s a belief that—even in the very collaborative media of TV and movies—a singular vision is preferred to writing by committee. Shows like Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Babylon 5 and Breaking Bad and the first four seasons of The West Wing are based primarily on the talents of the singular vision of the person running the show who also did most of the writing or at least ran a very tight writers room (Joss Whedon, J. Michael Straczynski, Vince Gilligan, and Aaron Sorkin, respectively).

And yet, plenty of great shows—including all the iterations of Star Trek—are very much not that. For all that people talk about “Roddenberry’s vision,” the fact of the matter is that Gene Roddenberry has never been the singular vision of Star Trek except for The Motion Picture and the first season of TNG. The success of the original Trek is as much on the backs of Gene L. Coon and Robert Justman and Herb Solow and D.C. Fontana as Roddenberry, and he wasn’t even the show-runner for the third season.

One of the best written movies in the history of the world is Casablanca, which was written by about nine thousand different people with rewriting happening not just during filming, but after it—the iconic final line, “Louie, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship” was written after the film wrapped and Humphrey Bogart dubbed it in later.

Sometimes multiple cooks actually gives you a gourmet meal, and this is one such. Very little of Harlan Ellison’s actual script remains intact, but the spirit of what Ellison was going for is the heart of what makes the episode great. Unlike the very theoretical debates in “Tomorrow is Yesterday” regarding Christopher and his family, the impact of time travel here is quite real. The landing party is trapped on the Guardian’s world with the only way out an imprecise time portal. They have to fix history, particularly when they realize that the reason for the change is that the Axis powers won World War II.

And of course the choice Kirk has to make is to let Keeler die. The very same visionary woman he’s fallen in love with.

What makes this episode so great is what makes the best Star Trek episodes great: it’s about people. Kirk isn’t just saving history, he’s saving history by allowing the violent death of a woman he’s come to love. The stakes are both large in terms of the course of history, and small in terms not only of Kirk’s feelings, but also allowing a great woman to die before her time. Because Keeler is a great woman, even though her work in 1930 only affects a few down-on-their-luck people in lower Manhattan. But her compassion is what enables three time-displaced Starfleet officers to even survive in the first place. Yet it’s never that simple. As Spock says, her desire for peace is absolutely the right thing, but at entirely the wrong time, as war was the only way the Third Reich and its allies were going to be stopped.

And what makes Kirk a good captain is that he makes the choice to stop McCoy. He lets one woman die so that billions of others might live.

Warp factor rating: 10

Next week: “Operation—Annihilate!”

Keith R.A. DeCandido‘s Heroes Reborn eBook novella Save the Cheerleader, Destroy the World is now available for preorder. One of six novellas tying into the new NBC series, Keith’s tale will be released on the 20th of November, and can be preordered from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or Kobo.